Originally published in TEACH Magazine, 100 Years of the Williams Treaties Special Issue, 2023

By Krista Nerland

A treaty is an agreement between an Indigenous nation and the Government of Canada (and often its provinces and territories as well). These treaties do not generally have an “end date,” and are intended to be the foundation for a long-term relationship between the parties—a Nation-to-Nation relationship which requires each treaty partner to fulfill their rights and responsibilities.

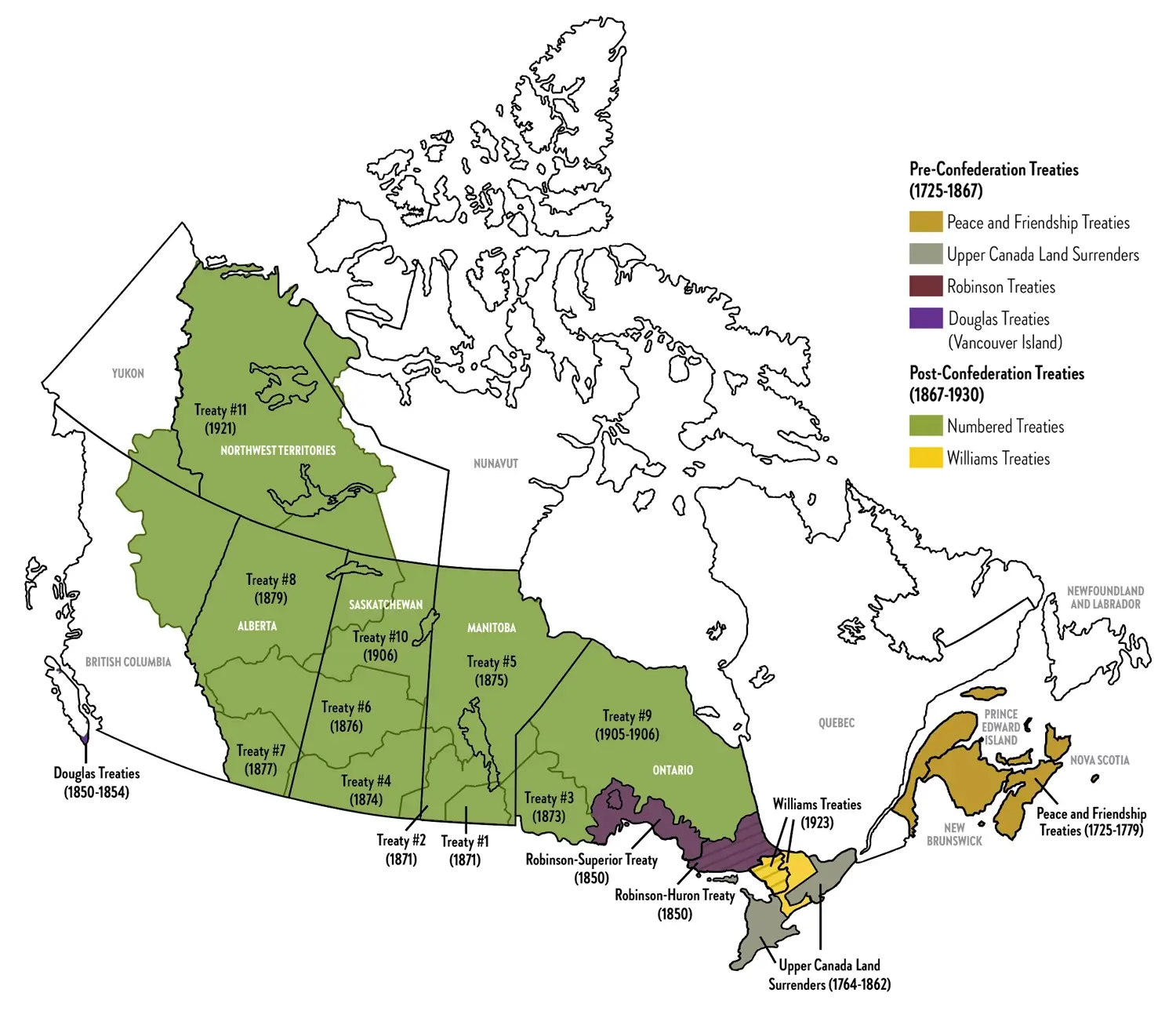

Phases of Treaty Making

1. Indigenous

(Time Immemorial)

Before there were any Europeans on Turtle Island (North America), there were millions of Indigenous peoples already living on these lands in their own nations. Those Indigenous peoples had their own laws and protocols for establishing treaties of peace and alliance with their neighbours. These treaties regulated how people interacted with one other, provided for shared ceremony, and promoted trade.

2. Commercial Contracts

(1600s)

When Europeans first arrived in Canada, the initial agreements they made with Indigenous peoples were commercial in nature. These agreements tended to be through fur traders working for companies like the Hudson’s Bay Company, rather than with European governments, and were built on Indigenous treaty-making protocols.

At this point, there were only a few of French and English fur traders in North America. Their small numbers and lack of expertise meant they were dependent on Indigenous peoples for their very survival. It was only by adopting Indigenous laws and processes for treaty-making that European traders were able to enter relationships with the local Indigenous peoples, and through this, gain access to their existing travel routes, trade sites, and furs. Indigenous peoples in this period tended to be focused on obtaining European trade goods.

3. Treaties of Peace, Friendship, and Alliance

(Late 1600s, 1700s)

As the British and French began competing for access to and control over North America, they focused on building alliances with Indigenous peoples who knew the landscape and had considerable military strength. In making these treaties, European powers continued to rely heavily on Indigenous treaty-making protocols.

Generally, for the Indigenous parties, the objectives of the peace and friendship treaties were to end hostilities with the British, facilitate trade, and guarantee that the British would not interfere with their land rights, harvesting, and way of life.

4. Territorial Treaties

(Late 1700s, 1800s)

Over time, especially after Britain defeated France and became the only colonial power on the scene, the context for treaty-making shifted considerably. In this period, Euro-Canadian governments entered treaties in order to gain access to Indigenous lands and resources, while also attempting to assimilate Indigenous peoples into Euro-Canadian ways. Indigenous treaty partners, on the other hand, were increasingly motivated to protect their resources, territories, and autonomy in the face of increasing pressures from Euro-Canadian settlement.

- Upper Canada Land Surrenders (1764–1862)

These were the first set of “territorial treaties.” They dispossessed First Nations of large portions of their lands in exchange for money. In the beginning, the Crown paid a one-time lump sum payment, but later, to save costs, a smaller payment was made once per year (this was known as an “annuity”). These treaties did not always establish reserved lands for Indigenous peoples to live on.

- Numbered Treaties (1871–1921)

Like the Upper Canadian Treaties, the written texts of the numbered treaties suggest that First Nations agreed to give up huge swaths of their land. In exchange, they were to retain rights to harvest on those surrendered lands, subject to the Crown’s right to use portions for settlement, resource development, and other purposes. However, the oral agreements set out by Crown negotiators and agreed to by First Nations signatories at treaty councils often bore little resemblance to the written texts. First Nations typically agreed to share their lands with settlers, but not to surrender ownership or their right to govern themselves.

5. Comprehensive Land Claims

(Mid-1970s Onward)

After the Williams Treaties concluded in 1923 and adhesions to Treaty 9 were made in 1929 and 1930, the Crown did not sign any more treaties with Indigenous nations until 1975. This is when Canada began entering into what we now call the era of “modern treaties,” after the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in the Calder v. British Columbia case that Indigenous land rights existed before the arrival of Europeans. After this decision, Canada set up a process of resolving First Nations claims about land that had never been surrendered through treaties—known as “comprehensive claims.” Since 1975, Canada has concluded 26 different modern treaties with Indigenous nations.

Modern vs. Historic Treaties

All treaties before 1975 are known as “historic treaties,” whereas the treaties that deal with comprehensive land claims today are referred to as “modern treaties.”

Generally, the historic treaties were brief and dealt with only a few issues such as reserves, harvesting, and annuity payments. The entire written treaty sometimes consisted of only one or two pages (though much more was often communicated at the treaty council than made it onto the written copy).

Some historic treaties were negotiated in a single evening; however, modern treaties are the work of decades. They are much more comprehensive documents, with clauses and subclauses that take up hundreds of pages. They often cover areas like:

- Ownership, use, and management of land, water, and natural resources;

- Harvesting of fish and wildlife;

- Environmental protection and assessment;

- Employment;

- Taxation;

- Parks and conservation areas;

- Social and cultural revitalization; and more.

While the historic treaties have a legacy of mistreatment and broken promises, the modern treaties have generally had a more positive impact. These treaties tend to recognize Indigenous peoples’ inherent right to self-government and create institutions through which that right can be realized. They also recognize the right of Indigenous peoples to decide what happens in their territories, and to benefit from economic development activities that occur there. Though there have been challenges with the implementation of modern treaties, the result still tends to be better opportunities and better outcomes for the Indigenous signatories.

A map of comprehensive land claims and First Nation self-government agreements can be downloaded from the Government of Canada’s website.

Why Are Treaties Important?

When Europeans arrived on Turtle Island, Indigenous peoples were already here. They had governments, laws, religious practices, and territories in which their people lived and their laws operated. They had sovereignty—the power to govern their people and their land.

The starting point for understanding why treaties matter is understanding that Indigenous peoples have sovereignty on this land, and they never gave it up. They did not lose it to the European powers in a war. They did not agree to surrender it to the Crown.

Over time, more and more Europeans came into North America. The country we know today as Canada was created. But as it grew and grew, it never really addressed the fact that the land on which it was based had first belonged—and continues to belong—to someone else.

Treaties are important because they create the blueprint for a relationship between Indigenous peoples who never gave up their right to govern this land, and the newcomers who now live on it. If the Crown and the newcomers respect the significance of the treaty relationship and the sovereignty of their Indigenous treaty-partners, treaties can provide a foundation for all of us to live together on this land in a positive and meaningful way.

What Does the Phrase “We Are All Treaty People” Mean?

This phrase refers to the idea that both non-Indigenous and Indigenous peoples living in what is now Canada have rights and responsibilities that arise from the treaties between their nations. Every road, building, home, school, hospital, etc. in an area covered by a treaty was made possible because of that treaty. Every non-Indigenous person who lives on treaty lands is there thanks to a treaty.

Treaties provide a potential framework for co-existence on the land that is now called Canada. But for this to work, the Canadian government and its citizens need to engage seriously in the process of treaty renewal—including by recognizing Indigenous peoples’ continued rights to govern themselves and make decisions about their territories.

Krista Nerland is an associate at Olthuis Kleer Townshend. Her practice focuses on litigation related to Aboriginal rights, Aboriginal title, and treaty rights; human rights and discrimination; and advancing Indigenous jurisdiction.