By Dr. Kara Stern

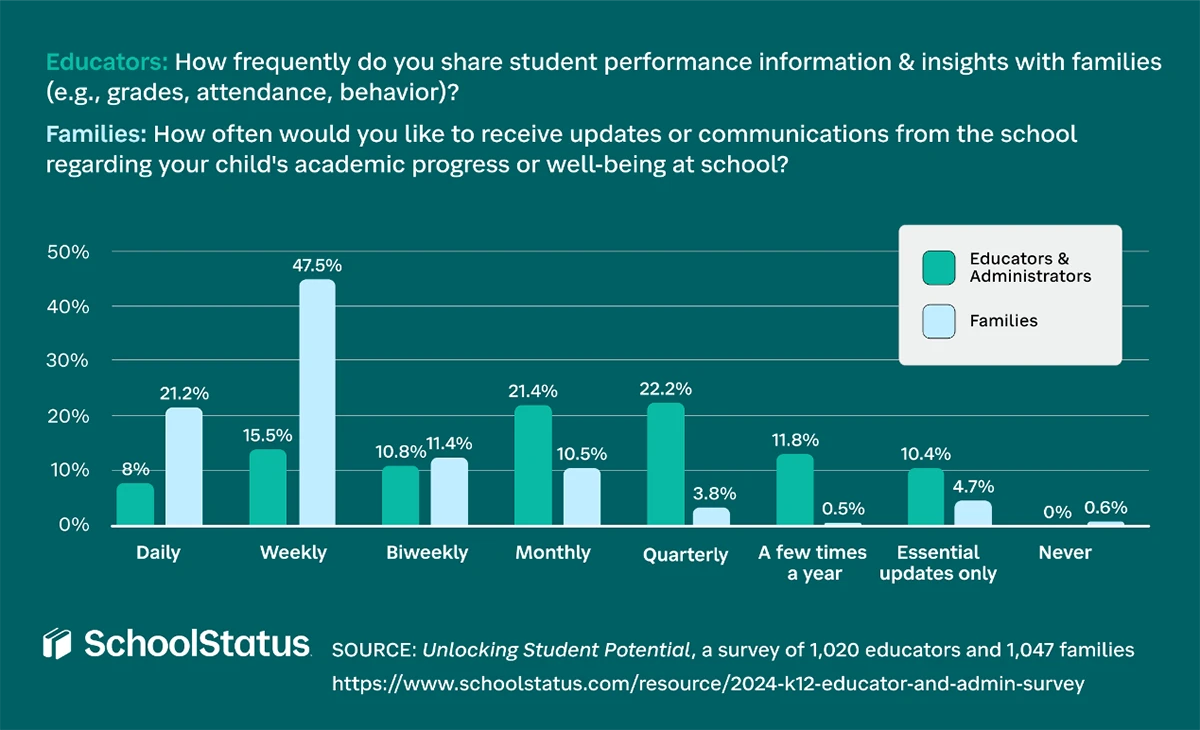

I recently helped analyze survey data from over 1,000 K–12 families about what they want from schools, and this insight stopped me cold: parents are asking for more communication than we’re giving them. They want positive updates about their children, regular information about academic progress, and, crucially, proactive communication about attendance before it becomes a problem.

That last point matters more than we might realize, because attendance is about relationships, not just policy enforcement or automated calls home. When parents and guardians trust that their specific child’s presence matters to their teacher, they will move mountains to get their child to school.

Trust builds through consistent, meaningful communication that shows families you see their child as an individual, not just a name on your roster. As a school leader, I once designed a support program with one struggling student specifically in mind. After months of development and approval, I sent a school-wide email announcing the program. Applications poured in, but that one student’s mom didn’t sign him up.

At the next PTA meeting, she mentioned being disappointed she hadn’t heard about the program. “You received the email,” I said. (I had checked, of course!)

Later, she pulled me aside: “You knew we needed this. You should have called me.” At the time, I was annoyed. In hindsight, she was absolutely right.

Not every communication needs to be personal, but the ones that matter most do. When a child is struggling, when there’s an opportunity that could change their trajectory, when attendance becomes a concern, those moments require human connection, not mass distribution.

This year, instead of waiting for problems to surface, invest in the relationships that prevent problems from starting. Here are some tips on how to do so.

1. Begin with connection

Within the first few days of school, send families a “Welcome to Our Class” newsletter. Share something about yourself, what students will learn this year, and what excites you about teaching. Include a form asking families about their hopes and concerns for the year, what they’d like you to know about their child, and how they prefer to receive updates. Show families their input matters from day one and use their responses to personalize your outreach this year.

2. Educate about attendance like you would any other subject

Most parents and guardians don’t know that attendance patterns established in the first month often persist throughout the year, or that chronic absenteeism (missing just 18 days) can derail academic progress in ways that compound over time. Share this information proactively, the way you’d explain any other aspect of learning. When families understand the stakes, they become partners in solutions.

3. Make positive contact before problems arise

A quick email, text, or call about a student’s insightful comment or improvement on an assignment creates a foundation for harder conversations later. When you eventually need to discuss attendance concerns, you’re building on an established relationship rather than starting from scratch.

Research from Learning Heroes backs this up. Schools with strong family engagement see dramatically better attendance outcomes, with some studies showing around 800 fewer absences when relationships are solid before challenges arise.

Here’s what I wish I’d understood earlier in my career: parents aren’t asking for perfection from us or their children. They’re asking to be included, informed, and treated as partners in their child’s education. When we show them their child’s daily presence matters for belonging, connection, and the small moments that make school meaningful, attendance becomes a shared value.

When families trust that you genuinely care about their child’s success, they’ll do everything in their power to get that child to your classroom. And that’s when the real learning begins.

Dr. Kara Stern is Director of Education at SchoolStatus, where she works with districts nationwide on attendance and family engagement strategies. A former high school teacher, middle school principal, and head of school, she holds a doctorate in Teaching and Learning from NYU.