Originally published in TEACH Magazine, January/February 2025 Issue

By Carol Gutierrez

A double rainbow, yes. The first time you see the Grand Canyon or Michelangelo’s David, sure. An astonishing goal in the game’s last 30 seconds, definitely. This is the stuff that leaves you awestruck. But a herniated disc? Sounds unlikely, but that’s what did it for me.

I was recovering from a spinal injury last summer when I read The Power of Awe by Jake Eagle and Michael Amster, and it changed my mindset. The book blends scientific and sensory, talking about ways we can bring more awe into our lives using what the authors call the “A.W.E. Method”:

- A (Attention): Turn your undivided attention to things you appreciate, value, or find amazing

- W (Wait): Slow down and pause

- E (Exhale and Expand): Amplify the sensations you are experiencing

So, while I was resting at home during summer vacation, rather than relying on medication, I decided to use the lessons from The Power of Awe to help me reduce my pain. The book encouraged me to focus on all the awe I had before me: the view of the bay from my balcony, breakfast in bed, the movement of the leaves on the trees outside my window, visiting with family members, the extra time I had to read and learn.

The Hypothesis

The topic of awe itself couldn’t be more timely. After 35 years of teaching elementary school, I’ve never seen such an urgent need to address social-emotional issues in and out of the classroom as I do now, post-COVID. I began wondering whether the power of awe could help not just me, but my students as well.

My thesis was this: Even if we can’t teach awe itself—since it can’t be conjured or manufactured—perhaps we can teach the ability to recognize, tune into, and appreciate a sense of awe in ourselves and others. It could be worthwhile.

Research shows awe has both physical and mental benefits, from calming down our nervous systems and relieving anxiety, to encouraging the release of oxytocin—the “love hormone,” which plays an important role in social interactions. I hoped all this might help children connect to others and their world in a way that the pandemic had squelched.

To test my hypothesis, I came up with a project that I could try out with my third-grade students. I called it the Awe Share Fair. I even decided to email Jake Eagle, one of the authors of The Power of Awe, about it. He was quick to encourage me and thought the fair was a “terrific idea!”

The Exploratory Period

I began by asking my class what gives them a sense of awe. The room fell silent, students’ eyes unfocused and gazes far away as they sorted through memories. Their initial response made me realize that simply asking the question was perhaps as important as answering it, which kicked off a revelatory few months of exploration.

We decided to start by experiencing and identifying awe for ourselves. First, through a class discussion where we looked at awe-inspiring images—rainbows, ocean waves, whales, sunsets—and considered what emotions they evoked in us. Next, by exploring activities from Eagle and Amster’s book that would help us focus on moments of awe, such as watching movement, elevating our gaze, and connecting with nature.

Then, it was time to head outside and practice finding awe for ourselves. We put on our “Awe Goggles” (pretend glasses we handmade out of paper) and looked around the school garden. There, students noticed dew on the leaves, buds on the trees, designs in the tree bark, insects, hanging fruit, and patterns in nature. They were astonished at all the awe around them.

We kept going, relishing exceptional moments—such as our field trip to the California Academy of Sciences, where we got to meet an albino alligator and have butterflies land on us—along with simple day-to-day wonders, like memories of a family weekend.

The Interview Process

The challenge, then, was to articulate all this awe we felt. Some students were immediately opinionated and persuasive. Others stayed silent, not quite sure how to put their feelings into words.

So, we dug deeper: with interviews. For two weeks, students’ homework was to interview four adults about times that they’ve experienced awe, asking open-ended questions, probing for details, and writing everything down. This was where students learned the value of asking others about the topic and really listening to their answers.

They presented their results from conversations with family members, friends, and neighbors. The topics were diverse, the audience was riveted. Normally quiet students now had big voices. One talked about how his grandfather listens to Bob Dylan when he’s driving in the car. Another told the story of his family traveling to Texas to chase the solar eclipse earlier that year. He shared a photo of the tiny crescent-shaped shadows on his face and we felt his awe.

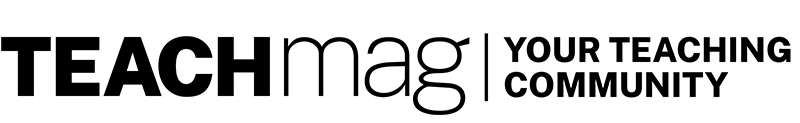

The Awe Share Fair

Then it was time for students to extend themselves beyond their immediate circle and create our school’s first Awe Share Fair. From a wide-ranging list of 72 examples of awe, which included things like baby rabbits and disco balls and walking in the snow and learning a new language, each student selected a topic that spoke to them. Their task was to create a visual display about their chosen topic and then showcase it to students in the other third-grade class. By presenting our topics to students outside of our own classroom, we hoped to further our understanding of awe’s possibilities.

This part of our project began the week the students took their first state-wide tests. Turns out, the research is right; awe is a great antidote to stress! The awe project was an invaluable, joyful release valve for students during that time. Then, once the testing window closed, everyone happily turned their full attention back to the Awe Share Fair.

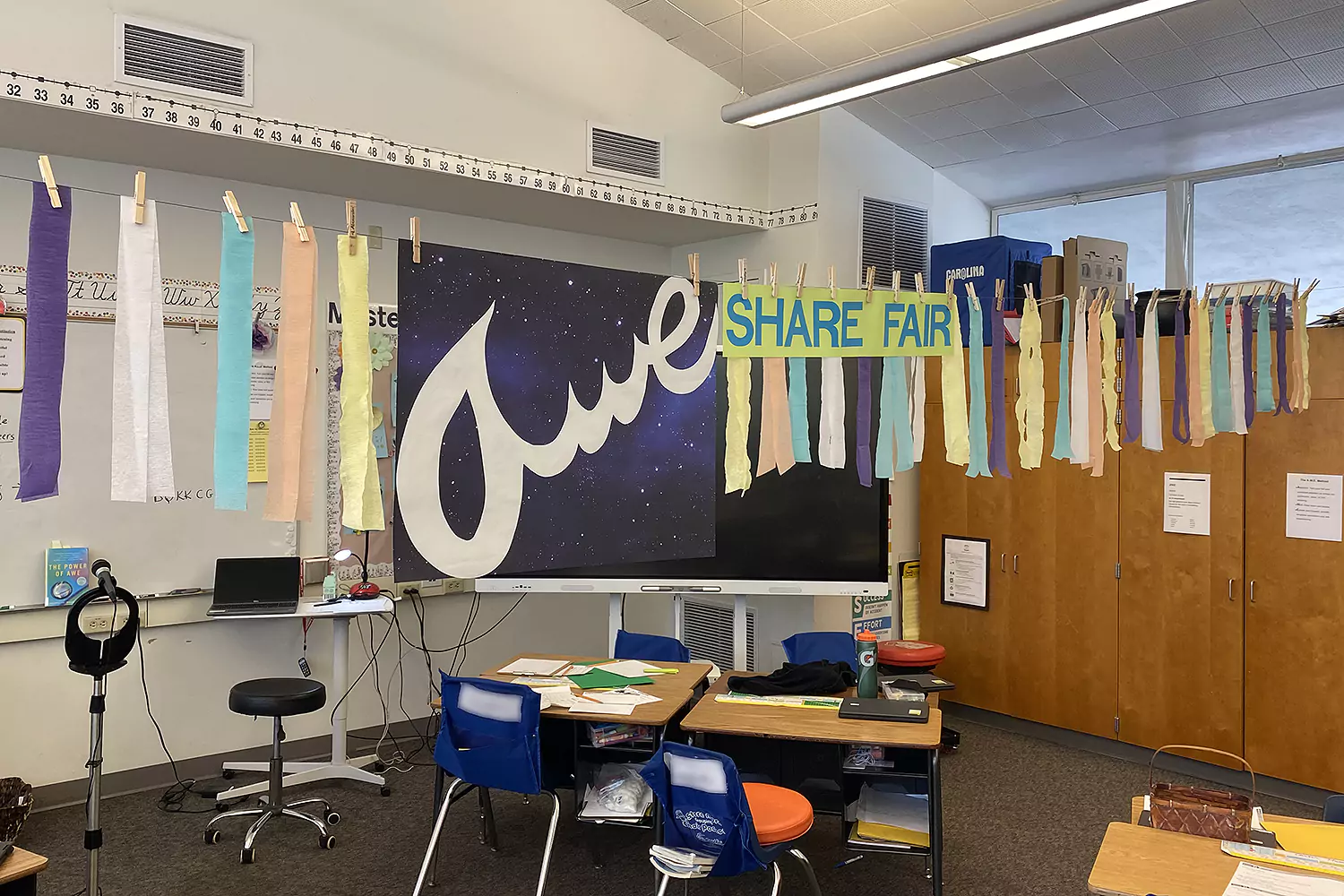

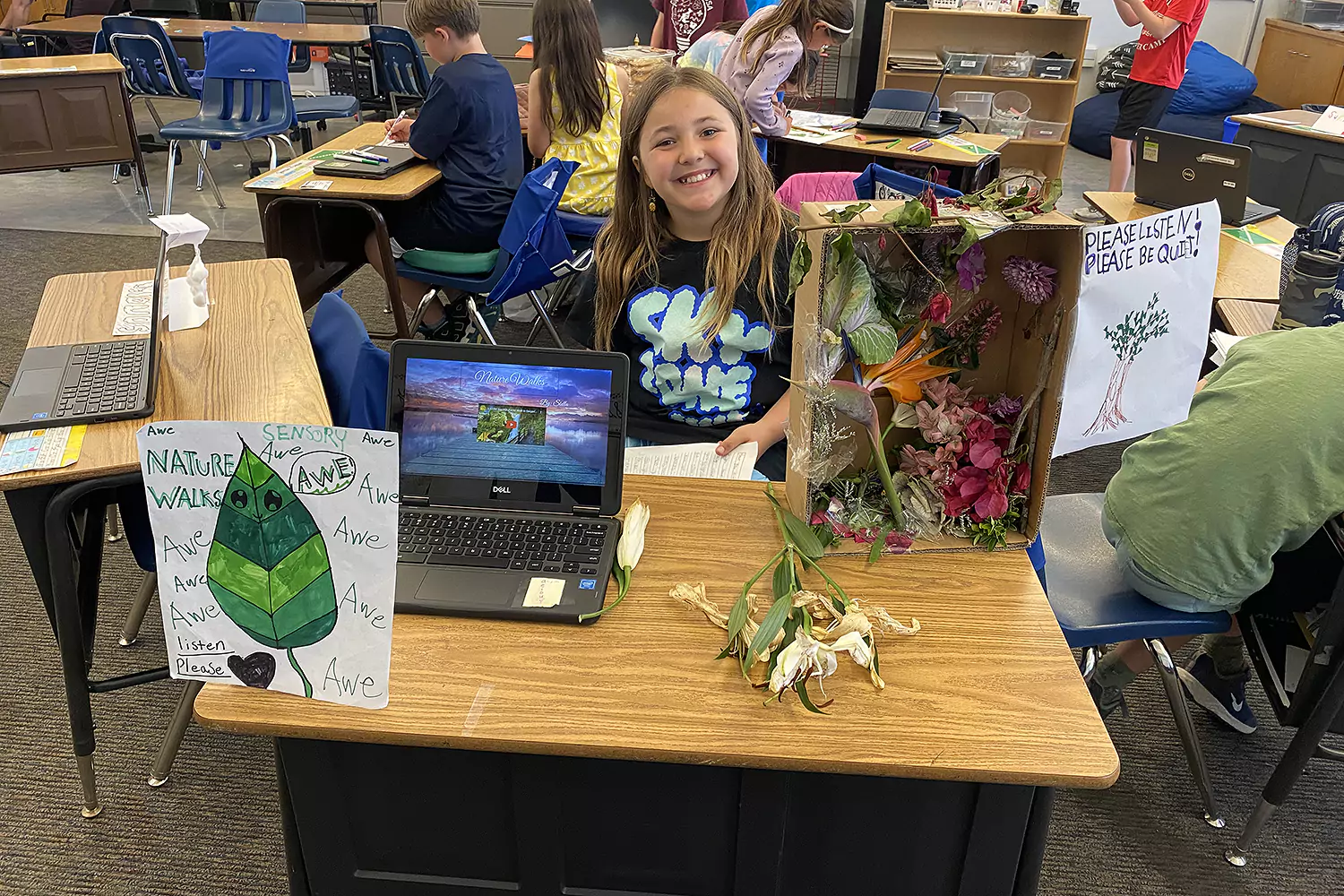

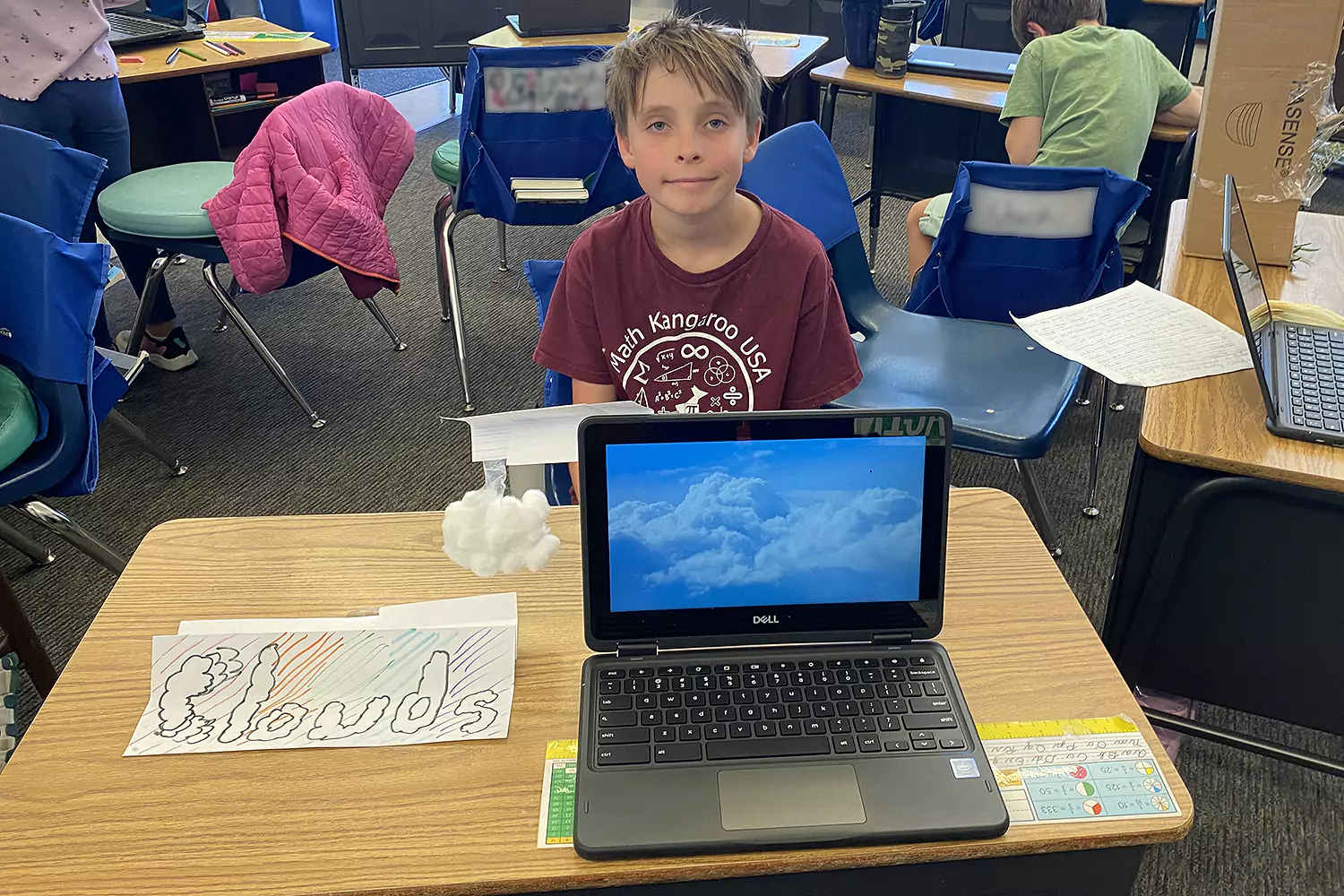

Suddenly, there were fragrant flowers adorning the desk that accompanied the “Nature Walks” display, cotton balls decorating the “Snow” laptop, and posters hung from the desk of “Imagination.” In one corner of the classroom was a poster about “Patterns in Nature” and in another was a spider web made of yarn. Each student found their own way to communicate a sense of awe to their audience.

The day of the Share Fair, as other third graders walked around our classroom, my students introduced themselves to each and every one who stopped by their desk. They talked about their topics, shared research, played videos, encouraged questions, and asked for feedback (important social practice, especially for shy or anxious students).

The Final Result

Awe might seem easy to convey. Show someone a photo of the Matterhorn and they’re wowed by the epic peak, right? But through this first Awe Share Fair, we learned that giving people a true sense of awe takes work—and thought! Foods that seem awe-some, like chocolate and zongzi (sticky rice treats), for instance, tend to derail conversation about them. It’s hard to listen well when you’re busy chewing.

So we tried again, removing distractions and improving the Share Fair’s layout, placing some presentations on the terrace outside the classroom in order to reduce the noise. Then we invited more guests: fourth graders, parents, staff.

After Awe Share Fair 2.0, the students felt even more pride as we debriefed and discussed our progress. By now, it was almost the last week of school. Classwork was all but finished and still, the students voted to have one more fair—this time for the fifth graders—on the last Tuesday of the year.

We kept adjusting, adding additional decorations and some background music, making further improvements to our presentations, and ordering more “You are Awesome” business cards to pass out as souvenirs to attendees. The process was every bit as important as the result. Finally, with Awe Share Fair 3.0, we achieved the fair we really wanted.

Then came the reviews: all good! Past students wished they’d had their own Awe Share Fairs when they were younger. Siblings, parents, and students—some who’d never stopped to consider awe before—talked about the wonder of the project. Everyone said they hoped to be invited to another fair next year, because they had enjoyed the experience so much.

The Power of Awe

Of course, awe isn’t new. Next generation science standards even call for curriculum about it. But I can tell you, there was something different happening in my classroom that year. The Awe Share Fair was unlike any other end-of-the-year projects I’ve encouraged, for three main reasons.

First, it gave every student a chance to shine. Science fair participants, for example, showcase specific skills, but with our awe project everyone contributed their voice. They also had the comfort of being in (or just outside) their own classroom. The only essential ingredient for success at the Awe Share Fair was true enthusiasm for something.

Second, at a time when devices and AI are encroaching on childhood, our awe project focused intentionally on human interaction. Students demonstrated their best speaking and listening skills from the interview to the presentation stage. Both improved markedly.

Third, undergirding the whole project was the mindfulness that can be derived from the “A.W.E. Method:” taking a few short moments to turn your undivided Attention to the things that give you awe, slowing down and Waiting, then Exhaling in order to Expand and amplify the sensations that you’re experiencing. This breathing practice helped everyone—from the student presenters to the Awe Fair attendees—get in touch with the feeling of awe.

When the project was done and the school year over, what impressed me most wasn’t just the diverse, deeply felt presentations by the students. It was the willingness of teachers, parents, and kids from other grades and classes to stop and really listen to my students describe the specific things that make them revel in the world around us.

You can’t plan to be awestruck, but you can practice being more open to wondrous moments. We can remind ourselves— and teach our young people—to embrace this mindset. Through the Awe Share Fair, my students and I explored the world, connected to science, reconnected with others, found new inspiration and purpose, eased anxiety, and most importantly, got young and old talking, speaking, and listening from the heart again. It was truly awesome.

Carol wishes to thank Holly Finn, class parent extraordinaire, for her help with the initial edits to this piece.

Carol Gutierrez is an elementary teacher in Hillsborough, CA, and a parent of three wonderful adults—Nik, Katie, and Joe—with her husband, Mike.