The Power of a Good Question: Prompting Critical Thinking in Students

Originally published in TEACH Magazine, May/June 2023 Issue

By Sunaina Sharma

What makes a good question? We ask students questions all day long, but how do we know they are actually helping students learn and, more importantly, getting them to think? Being able to think for themselves, and especially to think critically, is one of the most important skills students will ever use—both in the classroom and beyond.

Critical thinking is the process of objectively analyzing information to form a judgment. It requires students to read, consider, observe, interpret, evaluate, reason, and conclude, but then it also requires them to articulate their position and justify it, meaning students must be able to effectively communicate their thoughts and ideas. Critical thinking is a skill that is expected of today’s 21st century learners and is a pillar of many province and state curriculum documents.

Reimagining My Questioning Style

A good question always prompts my brain to think, and I wondered if it would do the same for my students. I began to consider what would happen if I changed the types of questions I asked. Was there a way I could invite students to construct their own knowledge?

To inspire curiosity in my students, I had to start by exploring how to transform my questioning style. In my inquiry, I came upon a critical thinking skills graphic that provided examples of different levels of questions to help students learn actively. The level six questions were exactly what I was looking for. These were intellectually engaging enough to have students reflect on what they already knew, and research to understand what they didn’t, in order to seek out an answer.

I was eager to try out some of these questions for myself, so after my Grade 9 class finished reading the short story Lamb to the Slaughter by Roald Dahl, I asked the students my version of a level six critical thinking question: “We know Mary killed her husband. If you were the detective investigating the case, what would you charge her with and how would you defend your conclusion to the Crown?”

I had students break into groups to begin forming their answers. I never gave them any additional prompts or suggestions. They began talking immediately, but quickly realized that they needed more information. First, they had to figure out the legal consequences of killing someone.

Out came their prior knowledge. Students pooled together what they already knew from watching movies or television shows, then determined that they needed to know the difference between manslaughter, second-degree murder, and first-degree murder.

Out came their devices. They Googled, read, and shared the definitions they found. Once each group had a good understanding of the terms, they moved forward.

Out came their textbooks. They reread portions of the story to analyze specific plot events in light of the new definitions they had learned.

Out came their ideas. Students expressed their opinions, listened to each other, debated, disagreed, and worked towards forming a collective answer. They took notes and some even chose to mind-map or use a chart to keep track of all their ideas. We then gathered as a class to engage in a whole-group discussion so we could hear each other’s thoughts.

Out came their voices. Students communicated their answers and instinctively provided evidence from the text in support. Because of the amount of thought that went into drawing their conclusions, students referenced page numbers from the story and sources from the Internet. They were confident in their final decisions and sought to convince their peers to agree with them.

Digital Technology as a Learning Tool

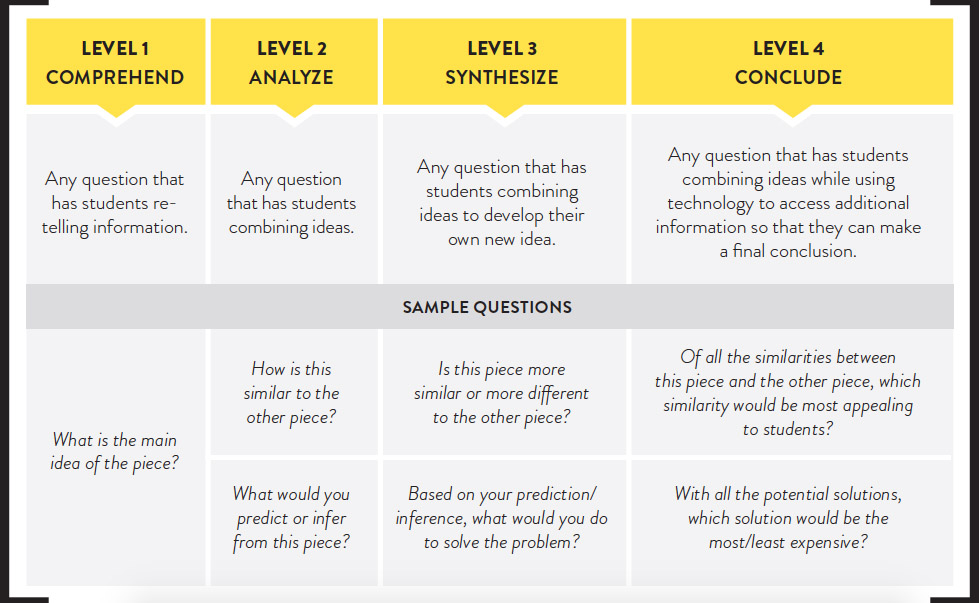

After the success with my Grade 9 students, I wanted to continue refining my questioning style. I also had the idea to try and combine asking effective questions with using digital technology. My own PhD research taught me that when students use technology to construct knowledge, it engages them. As such, I developed a graphic of my own to guide me and my students:

The graphic prompted students to use technology to access outside information that would help them answer questions. In addition, the four levels aligned with the four-level rubric in the Ontario curriculum. With this simplified graphic, I continued to ask my students questions that prompted their thinking.

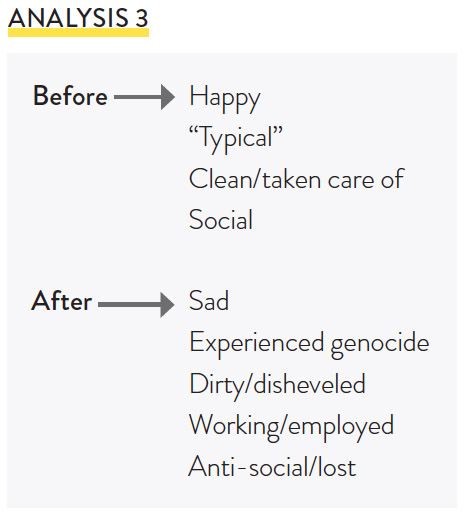

My Grade 11 students had been reading the graphic novel Deogratias: A Tale of Rwanda by Jean-Philippe Stassen. It is a text that has parallel storylines—one tells the tale of the main character, Deogratias, before the Rwandan genocide, and the other tells of his life afterwards. To understand the impact of the genocide on Deogratias, I engaged my students in an examination of traits he demonstrated before and after.

As students were contributing their ideas, someone called out, “After the genocide, he’s gone crazy.” I interjected and talked about the harm of that word, then asked the class to reconsider what adjective they would use to describe the main character. One student said, “I think he has PTSD.” I paused and asked everyone else what they thought. They couldn’t answer the question because they didn’t know exactly what post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was.

I divided the students into small groups and handed each group a blank piece of paper. I had them write “Does Deogratias have PTSD?” at the top of the page, then asked them to research the symptoms of PTSD and list them on their sheet. Students began to talk with each other and some even shared stories of a family member dealing with the disorder. After sharing what they already knew and respectfully listening to their peers’ experiences, students realized they needed technology. Some grabbed their phones and others borrowed a classroom device to begin exploring and researching.

Once they accessed reliable websites, students also started flipping through the graphic novel to look for evidence they could use to prove or disprove whether Deogratias had PTSD. Again, students accessed their prior knowledge, used their technological devices, reread their book, constructed their own ideas, and shared their voices with their peers.

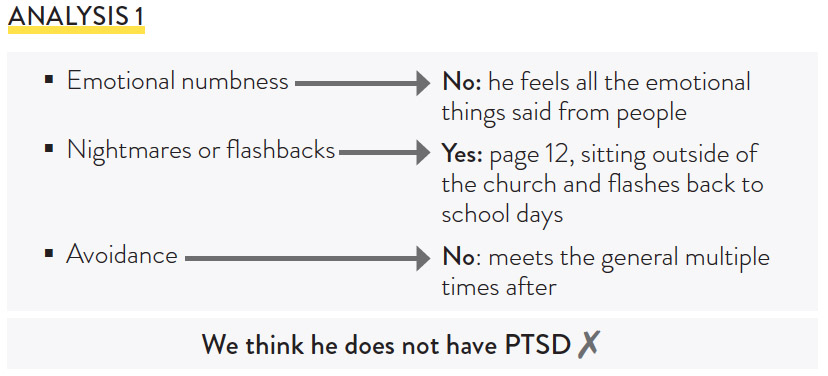

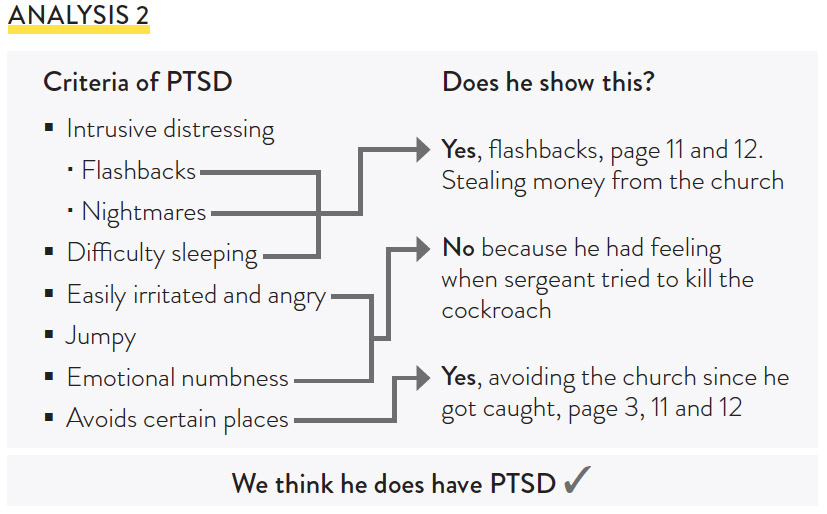

Here are some student responses to the question “Does Deogratias have PTSD?”

The Impact of Using Enhanced Questions

As educators, sometimes our passion for our subjects can lead us to get so focused on content that students are left wondering how their learning is relevant to the world beyond the classroom. But by reframing our questions, students are able to see the relevance of what they’re learning.

Asking students enhanced questions sparks their intellectual engagement. When we ask questions that prompt critical thinking, students are invested in choosing strategies to find the answer. They inevitably start by examining what they already know to act as a foundation for deeper learning, then they do a close reading of the text to analyze particular lines. They also use technology to deepen their learning, then form an opinion and justify that opinion with evidence.

What’s more, because they are so engaged, students are willing to share their ideas with others. They communicate, collaborate, and participate in active listening. Those are the skills I want to arm my students with because those are the skills they will use in the future.

Dr. Sunaina Sharma is an in-school program leader and secondary teacher with over 20 years’ experience teaching in the Halton District School Board. She is also an instructor and practicum advisor in a Bachelor of Education program, where she is able to share her classroom experiences with future educators.