Leveling Up: Motivating Students Through Gamification

Originally published in TEACH Magazine, November/December 2019 Issue

By Adam Stone

At Chapelwood Elementary in Indianapolis, Amanda Moore has turned to “gamification” to motivate her fourth-grade students.

Students use the Classcraft platform to build avatars, or virtual selves, and then earn points for completing lessons, helping classmates, or displaying other positive traits. “Whatever behaviour I want to see improve in class, I can reward points for that in the game,” Moore says. “Then they use the points to level-up their character, which means they get more armour and they look cooler.”

Grammatically, it’s an awful-sounding word: gamification, or as a verb, to “gamify” the classroom. Teachers, however, have found a powerful tool here. By leveraging technology and introducing video-game style interactions, some say they are able to grab kids’ attention and drive a higher level of enthusiasm.

At Michael E. Smith Middle School in South Hadley, MA, digital literacy and computer science teacher Lisa Manzi uses the Kahoot platform to help turn learning into points-driven fun. “They love it; they beg to play,” she says. “If I were to do just a straight-up review of concepts they would groan, but when you play it as a game, the level of energy is high. It’s fun and loud. There is cheering.”

What is Gamification?

Gamification asks teachers to incorporate an element of play into their repertoire, usually the kind of digitally-driven play that students experience in the world of video gaming.

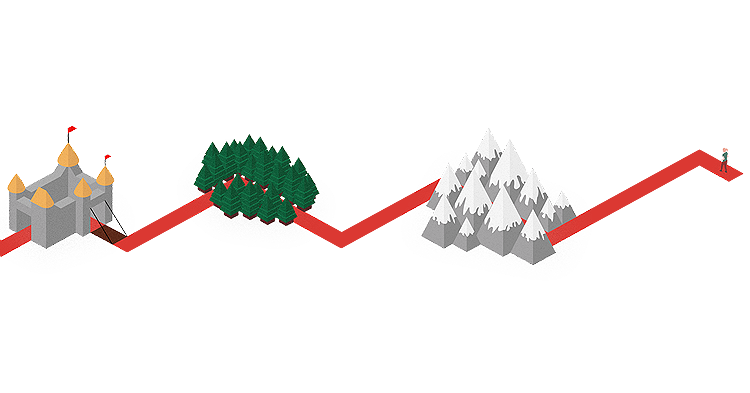

“At their core, games are giant learning engines,” says Endless CEO and founder Matt Dalio. “Games are a series of challenges that we scaffold our way up, to beat the big boss, to level up our characters and capabilities, to win, without realizing that we’re actually just learning.”

Gamification usually includes an element of competition—whether that is team versus team, or individuals working to beat their own personal best. “Most humans, especially young ones, love to compete,” says Tim Elmore, president of the non-profit Growing Leaders. “We want to try our hand at a game to see how we compare to a peer. Gaming allows kids to do this. Whether it’s a computer, or tablet screen, or a live game face to face, this raises the engagement in a subject. Regardless of the topic, kids want to win.”

While the outward forms of the games may vary widely, gamified classroom experiences will share a number of core traits, according to Dell’s Education Strategist Jeremiah Okal-Frink.

- Self-directed: “A game is driven by the gamers, the user—that is one of the key things. You’re looking for an experience where the action that is being taken isn’t just about following a procedure or instruction, [it’s about] some choice, some ability to make their own decisions.”

- Risk: “You are looking for an element of risk-taking or failing forward, this idea that you learn through the experience of playing. You don’t just read the instructions, play the game once, and then you’re done. It’s about playing it once, doing it again, failing and learning from that experience in an ongoing way.”

- Rewards: “In the traditional classroom there is already the idea of reward and consequence. In [a] game-based reward, you are gaining that badge or that level through the demonstration of a skill, or by getting through a series of challenges. It’s not the classroom idea of ‘here’s a sticker for completing a task.’ Gamification is about taking a competency-based approach to teaching and learning.”

- Fun: “People enjoy overcoming challenges and that can drive them, but if you don’t have that element of fun they won’t fully engage. What diminishes fun? Posting people’s rankings so that those who don’t rank as high may feel like they are struggling. Fun is having a ranking of the day, so that every day you start new and fresh. Having mini-projects or tasks, taking on roles, learning through activities. Fun is moving away from compliance and toward engagement.”

How it Works

Amanda Moore turned to gamification as a way to better balance her classroom time. “I was using a blended learning model, with my students online part of the day, and I wanted to make their independent time more productive,” she says. “I created online lessons for them and I needed a way to deliver that that was engaging and motivating and exciting. Just putting my lesson on YouTube wasn’t enough.”

Classcraft has a free version, but she pays about $100 USD a year for the upgrade, in which she can write adventure scripts to promote various traits and skills. She created a “realm” in which a villain has frozen the land; students use their math skills to un-freeze it. In another scenario, the kids search for a powerful healer to remedy a plague. At the end of the year, for the fourth-grade review, the kids will leverage all these learnings in an epic battle to defeat the villain once and for all.

“They get so motivated, to the point where they will ask me for extra work so they can earn more points and level up more quickly,” she says. Moreover, gaming has shifted the classroom dynamic. “When I am a ‘game master’ and not just a teacher, it breaks down barriers and helps us to build trust and deeper relationships. There can be a whole lot of stress in school, and this helps my classroom to become a positive learning place,” Moore says.

While Lisa Manzi has seen similar effects with her middle-schoolers, she says it takes some thoughtfulness up front to reap the full benefits of the game-based approach.

She assigns points for positive behaviours. First, she defines which behaviours she wants to reinforce. Then, she assigns students to teams. Last, she devises a point system that would be fair, logical, and highly motivational.

“You have to be consistent in how you award points, but you also have to tailor it to the individuals, and that is hard,” she says. “If I have a class that is noisier than another, they might get points just for having a positive day, for staying focused, and staying on task. In other classes it might be points for arriving on time.”

Manzi has also given a lot of thought to the down side of awarding points: what happens when a kid isn’t winning or cannot earn that magical badge?

“There can be meltdowns. There are some students who have trouble knowing how to make a mistake and then move forward. They get super-frustrated,” she says. The bright side is that it can be a learning opportunity too. “That shows me a lot about what we need to work on with that student. We need to support them so they can learn to make a mistake and bounce back from it.”

Overall, the use of technology in support of game principles has been a win for Manzi. “Many of my students had their introduction to computers and technology through entertainment and games. My challenge is to get them to use that as a tool for learning,” she says.

“If you can turn it into a game, that can open that door. It doesn’t have to be a ‘video game’—that [can be] a turnoff to parents and administrators—but you can use those same concepts: the challenges, the levels, the small successes as you build up to become more of an expert,” she says. “If you can build [it] into a classroom experience, that grabs the student’s attention.”

Making it Work

At Great Neck South High School in North Hempstead, NY, math and computer programming teacher Andrea Zinn asked her students create a game of their own. They used the techniques of artificial intelligence to create “bots”—computer programs that could compete in an elaborate version of the game Rock-Paper-Scissors, which is also known as “Rock-Paper-Scissors-Lizard-Spock.”

“An ‘interface’ tells you what program you need in order for your program to run. Students need to know how to implement the interface, and it’s not easy to come up with a decent assignment for that,” she says. A game setting made the concept more digestible. The motivation here: a round robin tournament in which the bots battled it out.

“On the day of the competition, you could hear [the students] down the hall, they were so excited and so into it,” she says. “They were really excited to see what had worked and what didn’t work. And it’s something tangible: they can see something that they have done and it’s not just in the classroom. It’s a competition, and they were really invested in that.”

In New York’s Oceanside School District, Angela Abend has brought the concept into the grade 4-6 gifted/enrichment program, using the Bloxels tool to help kids turn their narrative ideas into games.

“They incorporate writing, art, and design to create video games that are shared with other students and the Bloxels community,” she says. “The games are story based, with characters that they love. We talk about protagonist and antagonist. We talk about setting and conflict resolution. These are terms they know from traditional classes, but when they see a game aligned with those terms, it really increases the excitement and the energy.”

This intersection of academic concepts and a video-game style experience lies at the heart of the gamification experience. Teachers who have gamified say that by bringing a video game style experience into the classroom, they are able to inspire a new and different kind of engagement.

“They have been playing games forever,” Abend says. “Now they get to be in charge of it.”

For teachers looking to go this route, Stetson University education professor and video game expert Lou Sabina offers a word of advice: functionality counts.

“The most important practice for gamification… is to make sure your app and game actually work. When I was supervising teachers, nothing agitated me more—and the students in the class—than [when a] teacher… spends all of this time making a very detailed game and simulation, [but] when it [comes] time… to actually run… it, there are dead links, spelling errors, and mistakes that the students will pick apart.”

His advice? “Pre-test, pre-test, and pre-test.”

A seasoned journalist with 20+ years’ experience, Adam Stone covers education, technology, government and the military, along with diverse other topics.