Inspire Creativity with Headline Poetry

Originally published in TEACH Magazine, November/December 2012 Issue

By Chris Colderley

Teaching poetry to children is often considered one of the most tedious aspects of the language arts. One of my colleagues, for example, once lamented, “If you want to turn the kids off, just mention the word poetry.” But much of the disdain for poetry is unfounded. In fact, it’s a lot of fun. Children who dislike language arts find enthusiasm and zeal for poetry. Even those students who struggle with writing find success experimenting with different poetic forms.

From a pedagogical point of view poetry is a key to teaching reading and writing. Knowledge of figures of speech, for example, is critical to comprehension, developing voice, and creating imaginative and descriptive text. Literary critic and educator Northrop Frye claims, “If literature is to be properly taught, we have to start at its centre, which is poetry, then work outwards to literary prose… Poetry is the most direct and simple means of expressing oneself in words.”1

Poetry provides many opportunities to explore fresh ideas and to understand the world more deeply by changing the way the reader and the writer look at things around them. One of the initial challenges of teaching poetry is getting children to realize it involves a special way of looking at the world. Young poets need opportunities to understand that poems are everywhere even in the smallest and most ordinary things. In her poem, “A Valentine for Ernest Mann,” Naomi Shihab Nye says:

poems hide. In the bottoms of our shoes,

they are sleeping. They are the shadows

drifting across our ceilings the moment

before we wake up.2

The idea that poetry hides all around is a concept foreign to many students and teachers. One method of introducing poetry and inspiring creativity is the “cut-up” technique invented in the early 20th century by Dadaist poet Tristan Tzara. The technique was later refined by artist Brion Gysin and used extensively by William Burroughs in his writing.

In its simplest form the cut-up technique takes a page of text, cuts it into pieces, and rearranges the words and phrases to make new combinations. Burroughs described the technique in a 1964 interview: “Pages of text are cut and rearranged to form new combinations of word and images, that is, the page is actually cut with scissors, usually into four sections, and the order rearranged.”3

The unexpected juxtapositions from cut-ups have their own interest like the combinations found in visual collage. Chance plays a part, but the author selects from the new arrangements and eliminates pieces of text that lack meaning and coherence. Barry Miles, Burroughs’ biographer, claims cut-ups replicate “what the eye sees during a short walk around the block: a view of a person may be truncated by a passing car, images are reflected in shop windows, all images are cutup and interlaced according to your moving viewpoint.”4

The Process

A “headline poem” applies the cut-up technique to words or phrases from newspaper and magazine headlines, using them to craft a poem. There are several steps:

- Select some newspapers and magazines, leaf through them, and cut out interesting words and phrases from headlines. It is best to collect somewhere between 50 and 75 words and phrases from different sections to gather a range of vocabulary, as well as selections of nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs.

- Scatter the words and phrases on a table and look for themes, synonyms, rhyming words, etc.

- Arrange and rearrange the words and phrases on a page and read them aloud to check for fluency and impression. Because there is a visual quality to headline poetry, the placement of text can contribute to the presentation of ideas and meaning.

- When the desired order and placement of text is achieved, paste the words onto a blank sheet of construction paper.

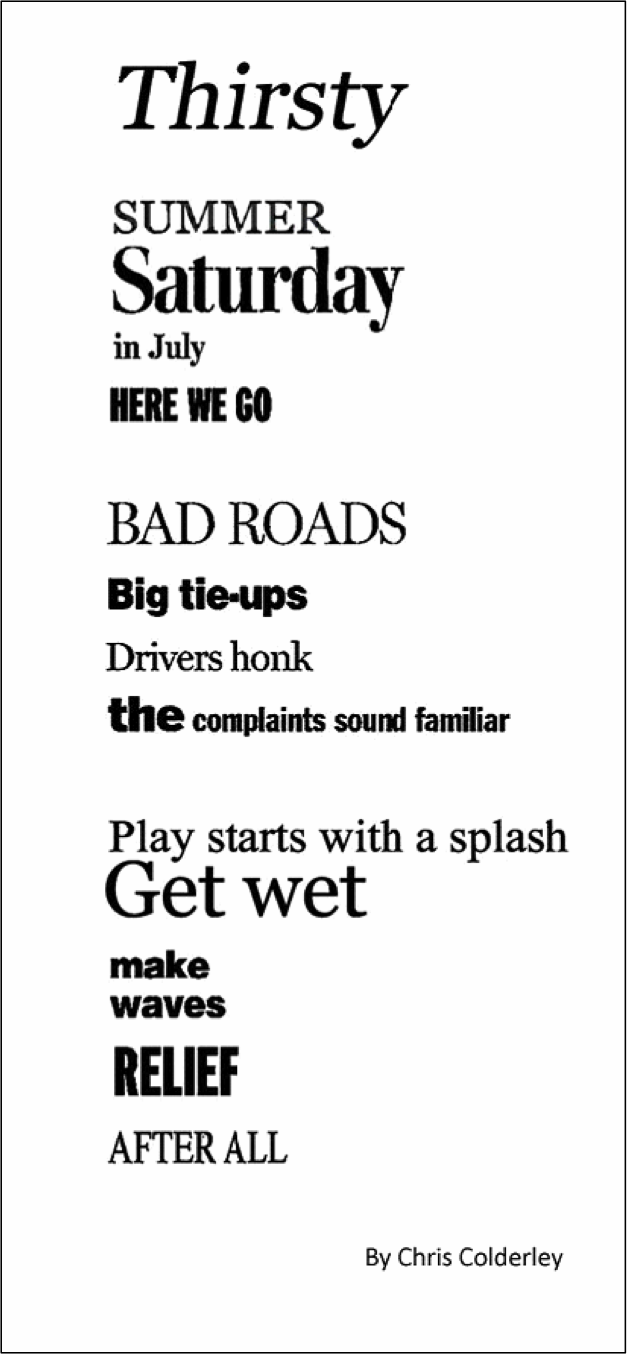

A completed headline poem might look like this:

There are several extensions that can make the poem more interesting:

- Access foreign language newspapers to add some flair to your poem

- Look for events that have a national or international impact

- Look for pictures, cartoons, and graphics that add to the visual quality of the poem

- Search newspapers and magazines from different areas and countries

- Use electronic media and technology, ranging from simple methods of cutting and pasting text with word processors to more complex manipulations with graphic programs, random generators, and slide show programs

- Use existing forms of poetry like acrostic, cinquain, or haiku to structure the arrangement of words and phrases

Headline poetry reinforces the idea that poems are everywhere, including newspaper and magazine headlines. The exercise awakens students to the possibilities of finding poetry in the language they hear and see every day. Crafting headline poetry also frees students to engage in creative activity without fretting over the blank page. In addition to giving students practice with the craft of writing, headline poetry also provides an outlet for children to explore creative processes and express their own unique views.

Chris Colderley teaches elementary school in Burlington, ON. He has conducted several workshops on teaching junior writers and using poetry in the classroom. He was awarded a Book-in-a-Day fellowship by poet Kwame Alexander for 2012. His work has appeared in Canadian Teacher Magazine; Inscribed Magazine; Möbius, The Poetry Magazine; Maple Tree Literary Supplement; Quills Poetry Magazine; and Tower Poetry.

1 Frye, N. (2002). The Educated Imagination. Toronto, ON: Anansi.

2 Nye, N. (1994). Red Suitcase: Poems. Rochester, N.Y: BOA Editions, Ltd.

3,4 Miles, B. (1992). William Burroughs: El Hombre Invisible. London: Virgin.